Foreign Correspondence XI

On Cristina Rivera Garza (and a note on the last season of Free Trade Island: The NAFTA Show)

Friends,

It’s been a weird few weeks in América del Norte, huh? Donald “Duck” Trump’s tariff-theatrics are straight from the play book of reality TV, which knows that the key to high ratings is to keep viewers guessing: Will or won’t he nuke the Mexican economy just for the lulz? Will he show mercy once again? Who will get booted from Free Trade Island first, Canada or Mexico? Stay tuned and find out!

Meanwhile, Claudia “Did you know she has a doctorate in climate science” Sheinbaum is also putting up her own show, though hers follows the logic of one of the classic telenovela sub-genres, the patriotic melodrama: Faced yet again with the specter of imperialism, the Mexican people put aside their differences and rallied ‘round the flag, armed with nothing save their dignity and their valor, ready to face the perfidious Americans, happy to know that their inevitable defeat will be glorious, because they are led by a stern yet benevolent stateswoman . . .

Both leaders are benefiting from the show, of course. They are not so much negotiating (can we speak of a negotiation when Mexico has bent over backwards to meet all of Trump’s demands, including deploying more than 10,000 soldiers to deter, detain, deport, and sooner or later disappear some of the most vulnerable migrants and refugees in the hemisphere?) as they are performing for the cameras, each giving their domestic audience what they want. I suspect that they will keep up the charade for as long as they can, Trump because he looks tough without having to actually blow up three decades of regional economic integration, Sheinbaum because, so long as Free Trade Island continues airing new seasons, anything bad that happens in Mexico can be blamed on the Americans. No wonder the two presidents have such a cordial relationship!

But what about the non-ideological stuff, the famous material conditions? I have no idea what’s going to happen!. It’s possible that the tariffs will never be implemented. It’s possible that they will come into effect at the end of the current moratorium. It’s possible that Trump will unilaterally withdraw from the USCMA—the treaty that replaced NAFTA—tomorrow morning. But my boss at Reuters, where I spent a year covering the oil markets, had a little motto that he would repeat whenever the Wall Street Journal or the Financial Times published a long piece about the future: Never predict the price of oil. So let’s sit with the uncertainty, shall we?

That said, I do know that a 25% tax on all Mexican exports to the US would cause unimaginable damage to my country’s economy. I don’t think most people in either Mexico or the US realize just how bad it could be. Consider two very basic figures: exports to the US account for approximately 30% of the Mexican GDP; during the worst year of the Great Depression, the US economy shrank by 10%. Do you see what I mean?

The point of NAFTA, its Mexican architects told my former nexos colleagues and me, was to diversify the economy, which until the late 1980s depended almost entirely on oil exports. This specialization meant that the country was vulnerable to the whims of the crude markets, but also to the policy and diplomatic measures of Saudi Arabia and company. Judging by that rather narrow criteria, the treaty was a resounding success: the Mexican people suffered immensely, of course, but at least now their fortunes wouldn’t be tethered to the price fluctuations of a single commodity. The problem, of course, is that today more than 80% of the increasingly wide range of products exported by Mexico are sold to a single buyer: the United States. In other words: Trump is the new OPEC. We’re oh so very fucked!

OK, we’re done with political economy! We’ll return to our usual literary programing after a brief word from our sponsors and a bit of comic relief. I present to you the anthem of Mexican neoliberalism, that long-dead beast that refuses to die:

Well now, that was uncomfortable. Let’s move on before I start rambling about how everyone should be buying gold.

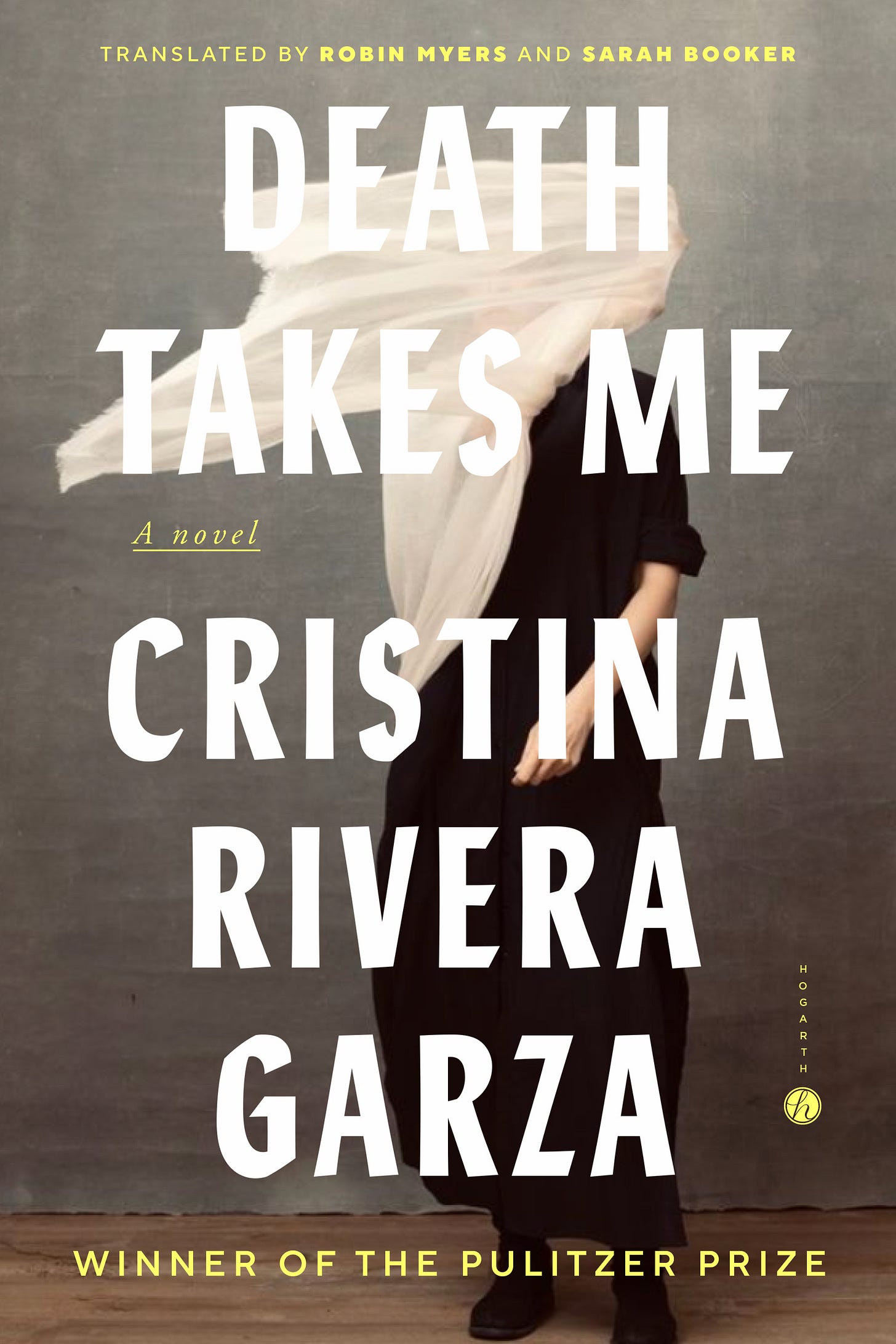

I’m writing today because The Atlantic just published my review of the English translation of Cristina Rivera Garza’s Death Takes Me, a batshit (by which I mean: really fucking good) novel about castration and the illegibility of poetry that won one of the Hispanophone world’s most prestigious literary prizes (and which I suspect will prove too modernist-weird for an American reading public that has come to expect fiction that reads like the screenplay for an HBO show).

First published in Spanish in 2008 under the title La muerte me da,1 the book purports to be about a series of murders of young men, but the truth is that it’s mostly about psychoanalysis, literary theory, and the Argentine poet Alejandra Pizarnik—and also secretly-but not-so-secretly about femicide. Here are two bits to whet your appetite:

The book’s unabashed intellectualism is the product of Mexican literary culture, which tends to abide by the Cuban writer José Lezama Lima’s famous motto, “Difficulty is the only stimulant.” But readers willing to play by Rivera Garza’s rules can expect a reward commensurate with their efforts, the sort of anti-noir novel that a ghostwriting team comprising Jorge Luis Borges, Jacques Lacan, and Clarice Lispector might deliver in response to a publisher’s request for a true-crime number.

Like the murders it recounts, Death Takes Me resists interpretation, inducing in the reader a disconcerting mixture of numbnes and anxiety. Those familiar with Rivera Garza’s more recent work will soon realize that the book has another, more political dimension. Although it approaches the issue obliquely by reversing the gender of the victims, Death Takes Me is the author’s firs sustained meditation on femicide—and perhaps a preliminary study for the memoir she would publish more than a decade later.

[. . .]

For all the numbness and the horror and the cerebral discussions of poetics, [CRG’s book] is also full of humor. It may well be that the novel’s most important contribution to our moment is that it consciously rejects the language of witnessing, elegy, and moral certainty on display in many contemporary stories about trauma. Death Takes Me, instead, suggests that personal grief and political anger can find expression, too, through ambiguity and irony—and even laughter.

That’s all for now, friends! Remember not to watch the markets and to smash your television into pieces.

Your Most Foreign Correspondent,

NMMP

The distance between the denotations and connotations of the original title (which CRG lifts from Pizarnik’s diaries [the phrase reads: la muerte me da en pleno sexo] and means something like “death gives me” or “death gives herself to me” or “death afflicts me” or “I caught death [as in: I caught a cold]”) and the one chosen by CRG’s translators (which means, well, the opposite of the Spanish!) tells you everything you need to know about the English version. Let’s just say that reviewing this book made me double down on one of my least fashionable positions: the translator is not an artist but a technician in the service of an artist. The beauty of translation is that it’s egoless—a service one provides to writers and their readers. Translators should be credited and paid handsomely and celebrated, of course! But they are closer to editors and audio engineers than to writers or musicians. Insisting that translation is an art form in itself, or even as some mystical process, has always struck me as a red herring designed to distract us from the fact that, if you truly have mastered the languages you work with, translation is an almost mechanical process. Not everyone can do it—in fact very few can—but that’s simply because very few people actually know two languages.

That video was really painful!