Friends, please forgive me for spamming your inboxes so soon after my last letter. It’s just that, while anxiously refreshing the New York Times homepage, I also did a last pass on my own English translation of an essay that I published in the special issue of Nexos that we published this January to commemorate the 30th anniversary of NAFTA. The piece will appear in a bilingual ebook that we’ll distribute free of charge, but reading it again, I realized that it will never again be as relevant as it is today. And so here it is, in all its un-copy-edited glory:

The Last North Americans

By Nicolás Medina Mora

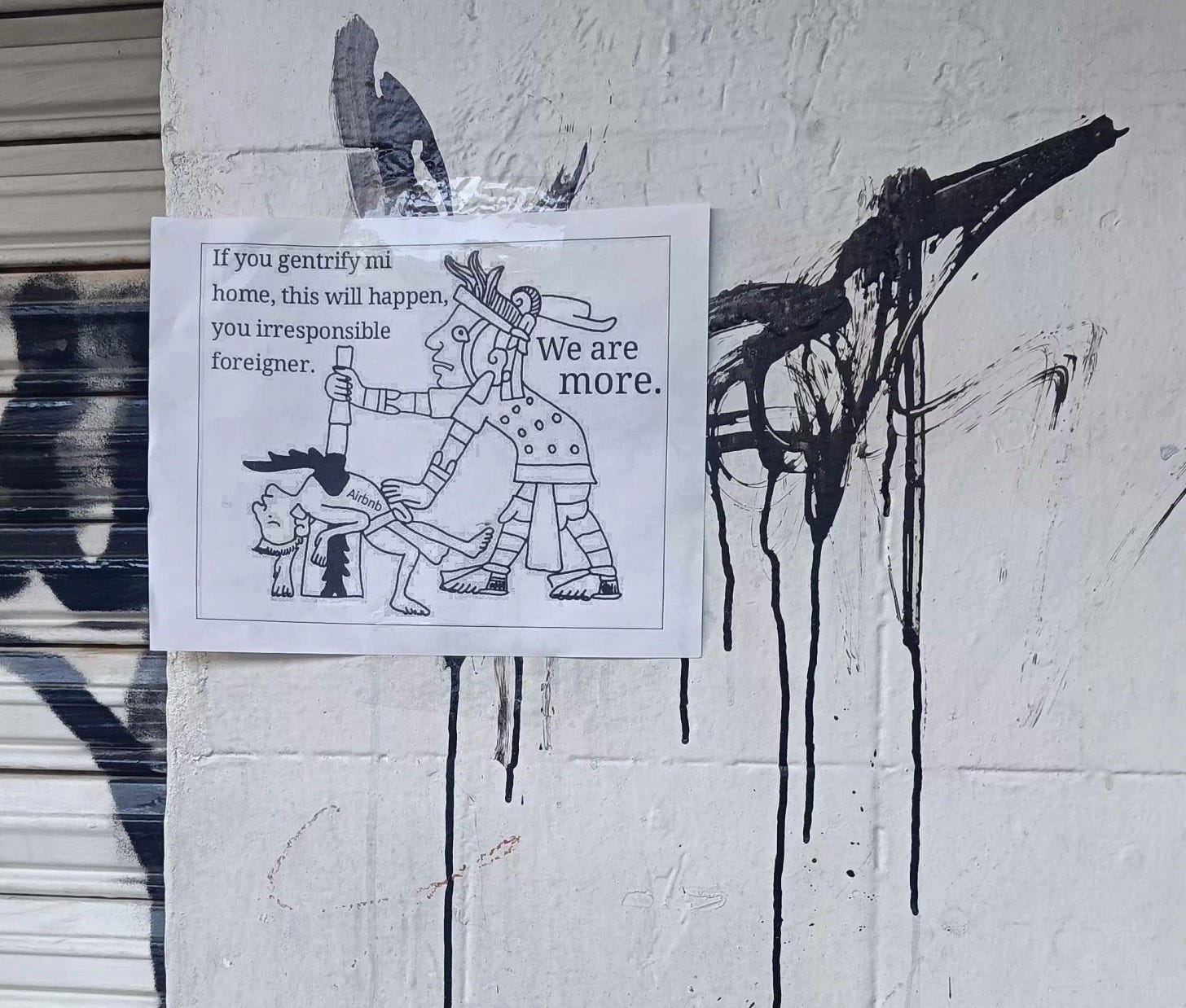

To call it a poster would be excessive: it was a sad sheet of white paper that had obviously emerged from the printer that some Young Urban Professional residing in the Very Young and Very Urban and Very Professional Colonia Roma, a rapidly gentrifying neighborhood in central Mexico City, had purchased during the terrible months when the home became an office. I promise this inference isn’t prejudice or caricature but the product of the most elementary journalistic deduction. It was obvious that this was the work of an amateur, someone who’d never wallpapered the hallways of the Faculty of Political Sciences with Maoist slogans, much less sweated like a Swede in a sauna while putting up placards with the face of some politician with dubious faculties and no knowledge of science. No, the experience in the arts of street propaganda of the person responsible for the sheet of paper extended, at most, to handing out photocopies of the adorable face of a lost puppy. Instead of a thick layer of glue applied as if it were varnish, or in the worst case a smattering of the most humble paste, the message had been affixed to a light pole with four pathetic staples.

That’s the extent of the details that remained in my memory. I don't remember the font, for example, though I'm almost certain it was banal (Times New Roman) or else hilarious (Comic Sans). In truth, my reporter’s honor demands I confess that I don't even remember the exact content of the message. It was written in English, that’s for sure, and more specifically in the good English that in Mexico betrays those who endured a private education: idiomatic, almost perfect, but plagued by diminutive errors.

What follows is non-fiction only in the sense of Montaigne, who declared (or could have declared) that his subject was not only what came to pass, but also what might have happened. Let's say (let’s pretend) that the sheet of paper I found stapled to a light post in La Roma said:

GO HOME YOU FUCKING GRINGO!!!

EVERYONE HATES YOU HERE!!!

YOUR [sic] RUINING CDMX FOR THE REST OF US!!!

DIGITAL NOMADS ARE A PLAGUE!!!

That, at least, was the spirit of the affair: an attempt at linguistic aggression that reached for violence but only managed ridicule. I’m certain that at least one gringo must have seen it and felt like the victim of a hate crime—but that gringo, too, would be ridiculous. This was not activism or protest, much less concerning evidence of a growing proto-fascist xenophobia among the English-speaking residents of one of Mexico’s most expensive zip codes. No, this was a rageful message in the co-op group chat where one of the owners complained that, ever since a neighbor had put his unit on AirBnB, the building had become the stage of scandalous orgies attended by coked-up blondes; a Yelp review cursing the servers at Contramar for daring to offer a menu in English to a proud citizen of the Mexican republic; a Twitter thread declaring, with the sanctimonious vehemence of a storefront preacher, that the gringos who move to Mexico City because it’s “cooler” and “cheaper” should live burdened by an almost metaphysical guilt.

The sheet of paper cursing the gringos of La Roma, in brief, was little more than a temper tantrum. But it was also something sadder, and deeper, and more revealing: the lament of a jilted lover. I would know. I’m the asshole who wrote the thread about metaphysical guilt.

It's been a year or two since I came across the anti-gringo poster, but recently I’ve found myself thinking about it almost every day. The reason seems obvious to me, though I suspect it might not to anyone else: In the course of preparing this special issue of nexos, my colleagues María Guillén, Valeria Villalobos, Julio González and I spoke at length with many of the Mexican architects of the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA).

These conversations forced me to question many received ideas that I’d accepted uncritically. For instance: the leftist commonplace which holds that the so-called “neoliberal technocrats” who ruled Mexico at the time of the negotiation were at best pragmatists without ideas and at worst cynics without values. The truth is more complicated and unsettling: the Mexican negotiators of NAFTA were something rarer, more beautiful, and far more dangerous: They were a congregation of utopians, a band of apostles, a vanguard party. The discovery that most surprised me, however, was the that the authors of the region's economic integration still believed in what we might call “the idea of América del Norte,” a beautiful concept that I’ve left untranslated for reasons that will soon become clear, and that in my eyes remains as far from being realized as the full communism of Lenin’s dreams.

But what is—or better: what was—this idea? I spent seven years writing a novel (in English, of course) titled América del Norte (in Spanish, of course), and for that very reason I don’t have the slightest clue of how to answer that question. Still, I suppose that, if someone held a gun to my head and demanded I define that nebulous cloud of contradictory associations in 280 characters or less, I would probably say something like this:

The idea of América del Norte is that Mexico and the United States have left behind the enmity that had divided them ever since the War of 1847, availing themselves of the equalizing power of treaties to become partners and friends.

The notion that economic integration would lead to transnational friendship has determined the course of my life to an extent that never ceases to baffle me. Like most members of the Mexican elite born circa1990, I was raised to inherit the New America that would take the place of the long-outdated Nuestra América (the name that the 19th Cuban revolutionary José Martí conferred to the sister-republics of the part of the hemisphere that was colonized by the Spaniards). It’s not a coincidence that the average thirty-something graduate of any private high school from the wealthy districts of Mexico City is incapable of parsing the syntax of Sor Juana’s baroque poems (or, for that matter, posting a sign) but always, without exception, speaks flawless English.

I’m afraid that my case is especially bad. At age 18, dissatisfied with my bilingual education—and desperate to put many miles between my tormented teenage soul and my father’s political career—I moved to the United States to go to college at Yale. My choice of school was anything but coincidental: along with Cambridge and Chicago (but not, interestingly, Los Angeles or New York), New Haven is one of the epicenters where the idea of América del Norte was born. Let's put it this way: one of the first classmates I met when I arrived at the university is an immensely likable guy named Sebastián Serra. His father, Jaime Serra, one of the chief negotiators of NAFTA, also studied at Yale, as did an economics professor who was known among my undergraduate classmates less for his former job—he was president of Mexico from 1994 to 2000—than for his rumored tendency to assign eight hundred pages of reading each week to those brave enough to enroll in his seminar on globalization: Ernesto Zedillo.

Why, then, was I so surprised to discover that the architects of NAFTA believed in an optimistic vision of the future born in the corridors of America's elite universities? Wasn’t it natural that a generation who went through the same positive experience as me—few places closer to paradise for a Mexican kid with an aristocratic last name and intellectual inclinations than Harvard Yard or the Old Campus—trusted the country that had welcomed them so warmly? Yes indeed. Except that the operative word of my last rhetorical question isn’t natural, but generation. Unlike our elders, I and other elite Mexicans who arrived in New Haven or Hyde Park during NAFTA’s second decade witnessed the rise of Donald Trump and his clique of dimestore Eichmans. After the 2016 presidential election, even the most privileged Mexicans living in the United States were forced to confront a truth that our class position had allowed us to ignore: a substantial portion of the people of our adopted country saw us not as partners or friends, but as despicable and dangerous inferiors.

It was a bitter lesson: the country we admired—whose language we had studied before mastering our own, whose culture we knew better than ours, whose people we loved as much or more than ourselves—hated us. As the narrator of my novel says to himself at the beginning of his descent into the underworld: “The problem at hand was not one of facts but of translation. América del Norte did not mean the same thing as North America.”

Hence, I’m willing to bet, the pathetic fury of the temper tantrum that some fool stapled to that light post. I have no way of knowing whether its author ever lived in the United States, but it wouldn't surprise me. I would know: there are few things more humiliating than returning to Mexico after living in America for ten years—and not by choice, but because a gaggle of white supremacists denied one a green card—only to discover that the hometown one did everything to leave behind is now full of gringos. Such is the tragedy of América del Norte: thirty years after NAFTA, Mexicans and Americans have yet to become equals. How many of us wouldn’t love to move to Brooklyn just for the sake of it, without having to perform highwire acts to secure a visa or a well-paying job, because the immigration authorities will never bother us and the salary we earn remotely is worth twenty times more in our adopted city than back home? In truth the affair is even sadder: How many of us wouldn’t love to move to Mexico City like the gringos do, not as a confrontation with demons but as an adventure, a long vacation?

Still, the fact remains that anti-American displays, such as the sheet of white paper or my thread about metaphysical guilt, often draw negative responses from other Mexicans. These reactions, I think, can be largely explained by the commonly held notion, accurate in many cases, that the people who complain most loudly about the gringos who’ve settled in some of the most expensive neighborhoods of Mexico City are privileged people. What right do we Young Urban Professionals have to denounce the gentrifying practices of our new American neighbors? Even if we assume that the newcomers are far more numerous than what the official statistics suggest, blaming the housing crisis of a city with half as many inhabitants as the entire state of Califonira on a handful of foreigners is evidence of class blindness. Conflating the vast capital with a handful of central districts is only possible if one, like your correspondent, only rides the subway in the course of a journalistic investigation into its decades-long decline.

It’s undeniable that the ancient Romans, displaced by the barbarians of the North, in turn displace less fortunate residents of Mexico City. But if we leave aside the spillover effects of rising rents in La Roma, the seed of political lucidity that hides at the core of my peers complaints becomes easier to see: Even those Mexicans who benefit from unfair advantages have fewer rights than a group of Americans who, in the context of their country, often enjoy fewer privileges than we do in ours (and who, it must be said, often remain conveniently unaware that the average wage in Mexico City is 3,000 dollars per year, which means that a salary that would be precarious in New York puts them in the wealthiest 1% of their adopted home). The white sheet of paper stapled to the light pole makes a crucial point, even if the form in which it expresses it is undeniably embarrassing: It doesn't matter how rich or how white you are or whether you went to Yale or Harvard, at the moment of truth, gringos are still gringos and Mexicans remain Mexican.

I’m not asking for anyone's solidarity. My grievances and those of my peers are so unimportant that they don’t deserve more public attention than I’ve already given them in this essay. What I want to suggest, rather, is that these complaints are a superficial symptom of a deeper reality: América del Norte as a community of equals never existed except in the minds of the Mexican architects of NAFTA. The gringos who move to La Roma are not usually Trumpists—many of them have told me that their decision to leave the United States had a lot to do with the election of that orange buffoon—but their presence in Mexico City offers incontrovertible proof that the asymmetry which the treaty was meant to resolve is still very much alive. If América del Norte indeed exists, my peers and I are second-class citizens of the new transnational homeland. It goes without saying that the vast majority of Mexicans living in the United States—or in Mexico for that matter—are noncitizen aliens of that imaginary realm.

All the same, there’s something undeniably unpleasant—or, to quote one of the Twitter users who replied to my unfortunate thread, something “in bad taste”—about the tantrums of the Young Urban Professionals. If resentment, so close to hatred, is always hateful, the resentment of those whom the majority resents is doubly so. Consider, for example, an unfortunate incident shortly after my repatriation. Two of my old college classmates, people who I had very much liked back in New Haven, were passing through Mexico City and stopped by my place to say hello. Less than an hour after they showed up, I was already asking them if they could tell me the year when the Mexican American War began. They couldn’t—could you, Idle Reader?—but the date I spat at them after they failed the stupid exam to which I’d subjected them wasn't the right one either.

I’m telling you all of this in hopes of explaining the sympathy I feel for the author of such an unsympathetic document as the sheet of paper stapled to that light pole. Few things embarrass me more than the way I treated countless American friends (some of them now ex-friends) in the months of depression (which is to say: the months-long temper tantrum) that followed my return to Mexico City. None of them—especially one of them, who will know, if she ever reads these lines, that this essay is a letter of apology—deserved to become the scapegoat for the pain that the collapse of the North American utopia inflicted in my heart. Were my American friends ignorant of all things related to Mexico? Much more than the majority of Mexicans in relation to the United States. Were they unaware of the unfair advantages offered to them by their blue passports? Almost as much as I and my peers are unaware of the unfair advantages of our surnames. Were they responsible for US imperialism? Yes, but they weren’t guilty of its causes or consequences.

Contrary to what I wrote in that unfortunate Twitter thread, the fact that one has benefited from the crimes that others committed in one's name means that one should be accountable, not that one deserves punishment. My friends owe me answers, as all Americans owe them to all Mexicans. But to pretend that a person one claims to love should bear the blame for everything that has happened since 1847 is, besides neurotic, ridiculous. The gringos of La Roma may be naive, unaware of their privilege, unwitting traders profiting from the foreign exchange, even bad neighbors. But they are not—in any way—a plague.

This last point is a recent conclusion for me. During the first years after my return to Mexico, I couldn't come across a gringo in the street without trembling with rage. How dared they set foot in my city while, at that very moment, their government was tearing children from the arms of their parents and interning them in concentration camps? Things got to the point that an artist friend and I began to sketch a performance in which we would walk around La Roma dressed in a blue uniform that would have the word HIELO embroidered on the back. Each time we saw a gringo, we’d approach them and shout, in artificially accented English: Show me your papers! If the gringo in question had with him a child-gringo, the script would switch to a parody of the inscrutable lingo of Mexican human rights activists: Is that person in a situation of infancy your person in a situation of infancy? Prove it with papers or we'll take them away from this situation of vulnerability!

The performance never happened, though not for the reason that I would have liked—what kind of psychopath thinks it's okay to subject a father or mother to such a cruel joke?—but rather because my friend and I realized that impersonating a police officer is a felony that the Mexican criminal code punishes with years in prison. In any case, and to my shame, the little piece of street theater that never happened is a perfect emblem of my feelings at the time: the anger, grief, and jealousy of an ex-boyfriend who really needs to go to therapy, because his jilted love risks mutating into hatred.

Hence the surprise I felt a few months ago, when The Nation, a magazine to which I sometimes contribute, asked me to participate in a panel on Mexican politics attended by a group of subscribers who’d come to town on one of the guided tours with which the publication offsets the loss of advertisement revenue. While answering a question from the audience about what Trump's second candidacy looked like from Mexico, I found myself saying something that two years earlier would never have left my lips: I have faith in the American people.

In the days that followed, as my psychoanalyst can attest, I turned the phrase over and over in my head, trying to decide whether it was a lie motivated by a colonial subject’s desire to feel accepted by his betters or a lapse of involuntary sincerity. I wound up leaning towards the second option: I do, in fact, have faith that the American people will not elect Trump a second time. Faith, of course, is not synonymous with certainty: one can only have faith in the face of uncertainty. I wouldn't be surprised if the orange clown returns to the Oval Office—trust me, I would know—but now that the bruises I developed in the course of my quarrel with the most imaginary of imagined communities are beginning to heal, I can finally say that my jilted lover’s resentment has faded.

I will never trust her again—fool me once, shame on you; fool me twice, shame on me—but today, thirty years after her birth and thirty-three after mine, I’ve finally managed to forgive my ex-girlfriend, América del Norte: that idea in equal parts beautiful and false, that unrealizable utopia, that collection of counterfactuals, that ouroboros of contradictions. I can only hope that she, too, will one day find reason to forgive me. Knowing that our love has left to never return gives me peace; may the certainty that our separation is irreparable also bring her closure. For at this point there’s no denying that I and the rest of my lovesick generation—the privileged Mexicans born at the same time as NAFTA, including the imaginary author of that sheet of paper—were at the same time the first and the last North Americans.

Mexico City, January 1, 2024.